groundwork of Groundwork

- groundworkbooks

- Jun 9, 2016

- 8 min read

At the open house at Groundwork Books during alumni weekend our classic sign got a new layer of paint. A photo was posted online and we learned that the logo was designed by Charyn Segal and Lincoln Cushing.

It was Lincoln Cushing humself that shared that bit of knowledge. Lincoln, a political poster designer and archivist, was involved in the original Groundwork Books project starting back in 1973.

Wanting to learn more about the groundwork of Groundwork Books (see what I did there mhmm) I reached out to Lincoln and he was happy to share some details.

From an OG (original groundworker) humself, Lincoln Cushing:

So, here's the true origin story as I know/remember it.

I arrived at UCSD (Muir) the summer of 1972, and got involved with several projects like the Muir Five and Dime coffeehouse and the Student Educational Change and Development Center (SECDC).

Late spring of 1973 I wandered into a storefront in Solana Beach where folks were building shelves and tables. I believe that the main carpenter was a guy named Jim Bell, who was active in early environmental planning at SDSU. It was to be a political bookstore, and I was excited. I do not remember what it was to be named. I agreed to get involved after the summer, because I would be out of town. During the summer one of the organizers, Roberto Riley, told me that there had been a split already (this was the early 1970s, after all) and that some of the people were going to set up a shop in downtown SD because "that was where the workers were." Others (himself included) were going to stay near campus, choosing to reach student radicals. The half that went downtown (I believe their store was on Broadway) were called "Changing Times," although we derisively called them "Changing Crimes." We never communicated or interacted.

Photo: Changing Times advertisement from North Star (Vol. IV No. 5 Nov. 12-25, 1973)

When I got back to SD, the group that located on campus was called "Groundwork Books." Members included Roberto, Chia Towner (Roberto's partner), Charyn Segal (later my partner), a disabled Vietnam Veteran (whose name I forget - maybe Bill), a woman named Kathy (Atkins?) (who lived in a collective in Solana Beach called Sun Dragon Farm and eventually left to learn printing at Cal Poly), and a couple of other folks. Only some of us were students. We met pretty much weekly. The goal of the bookstore was to spread propaganda. We defined ourselves as soft Marxist-Leninist with a hint of Maoism (although we'd never say that).

Monty Kroopkin, more on hum later on, remembers this political allegiance a little different.

"Actually I recall that one of the main issues of the split was that there were members who were more in the Frankfurt School, critical Marxist tradition and also some of the "libertarian" tradition of socialism (working class anarchism). The "downtown" faction did not want books of that sort to be sold at the store. The Groundwork faction did want those types of books and literature sold at the store. Rick Nadeau was one of my best friends then and for decades after. He was a militant supporter of having books by Marcuse and Chomsky (et cetera) included at the store. At any rate, it is accurate to say that the faction that became Groundwork (and the original Changing Times collective) was more politically diverse, and not only Marxist-Leninist tendencies," Monty said.

There is somewhere like, a billion of these in the Groundwork library.

Chia Wood chimed in on May Day 2017 with a few extra details:

We occupied the Solana Beach store for awhile after Changing Times left, until the owner sold the spot. During that time, Chip and Lee were important contributors. It's probably just as well we lost our space, because the split left us with $400 in inventory and in a poor position to pay rent. Roberto and I drove up to one of the distributors in LA and attended a meeting of their collective. Our request for credit was granted, and that was critical. Now back to Lincoln's story.

We did not have a place on campus, we were not yet a student group, so we had a giant metal rack bookshelf on wheels that we kept in a SECDC closet on Muir College. Every week, Monday-Thursday from 10:45 to 1:15 we would roll the cart out. I know that I went over to Revelle Plaza (a long push!) but I also know we used to be at the Muir Quad. This went on about a year. Our mailing address was the house where Roberto, Chia, and Charyn lived, 7777 Ivanhoe Ave, La Jolla.

When they built the new student center (1975?), we were a student group and got a nice corner space. We even recycled some of the Solana Beach wood I'd stashed to build shelves and benches. It was not long afterwards that we started to get progressive faculty to order textbooks through us, a huge boost to our visibility and bottom line.

That's it for origins, I have more on operations later. I'll send some newsletters and posters.

Long live Groundwork Books!

That's some impressive history right there. Radical UCSD and SDSU students hanging out, together, in Solana Beach. Solana Beach.

Yes, this place. A radical bookshop. Here. 40 years ago. (Actually more like right here.)

Lincoln had also written about the history of Groundwork Books at UCSD and another student group the Course and Professor Evaluations (CAPE). I'm lifting it here for those too stubborn to follow a link to Lincoln's Socialist Ideals article in the UCSD Alumni publication Looking Back:

In the ’70s, some new student project, destined to change the world, got fired up almost every week. A peer crisis center opened in the Muir apartments (Crisis K2) and a student-run coffeehouse was launched in the Muir Commons (the Muir Five-and-Dime) where cheap movies and hot cider were also on offer. We started a Student Print Co-op with cast-off equipment gladly provided by the Campus Reprographics Department (to keep pesky students off their backs).

Two of those projects, however, have miraculously endured to this day—Groundwork Books and the Course and Professor Evaluations (CAPE).

Groundwork Books began as a radical community bookstore in Solana Beach but quickly split into two political factions. The portion composed primarily of college students decided that the UCSD campus was a reasonable place to set up shop.

From the beginning, we students saw the selling of books as merely a means to an end. Our true goal was to transform society, one bit at a time, through self-criticism and study.

Illustration: Lincoln Cushing, Groundwork cohosting "Harlan County, USA " (a film by Barbara Kopple) in 1978

And self-criticize we did, endlessly, rigorously and long into the night. No bourgeois tendency was left untouched, no liberal value unexamined. We strove to behave as new socialist men and women. It may sound pretty strange now, but at the time it was a baptism by fire that made us examine ourselves in new ways.

In between these ethical exercises we actually managed to run a bookstore. At first, we dragged books across campus on a wheeled metal rack. Then we got a student center space and were able to offer students an environment where they could buy textbooks as well as browse other related texts.

Classroom orders became our bread-and-butter, so much so that the official bookstore tried unsuccessfully to close us down. We broadened our selection, published a newsletter of recent arrivals, sponsored study groups, and hosted May Day celebrations. It was always challenging to keep the collective spirit alive with the steady turnover characteristic of student groups, but Groundwork is still going strong 31 years later.

Bumper sticker: Lincoln Cushing, 1981. There's a really interesting story that goes with this. Also interesting, Groundwork Books somehow managed to keep the same phone number for 35 years. Minus the area code change. Fear not, we stocked up on these! Donate a few dollars and we'll send you one.

The Student Educational Change and Development Center (SECDC) was also seeded at that time and embarked on an ambitious program to transform UCSD’s pedagogical foundation. I was the first director of CAPE and we saw it as a tool to gain more control over our academic lives, by providing data for selecting electives and by offering structured feedback to faculty about their teaching. We endured numerous technical challenges, including burning out a good many electric pencil sharpeners and spilling a box of punched cards used to run our program on the Burroughs B-6700 mainframe. We outraged faculty and baffled students. But eventually the idea began to take hold, after students started to see—and use—our published reports.

Remarkably, the administration supported our efforts, and by 1974 CAPE was the most heavily funded student organization, with a $16,800 budget coming from a special systemwide grant supporting undergraduate teaching evaluation.

The fact that these two institutions survive today is a testament to the spirit of students who actively seek control over their own environment. I can think of no more rewarding a legacy than their endurance.

Monty Kroopkin forwarded that Changing Times ad from the North Star newspaper. Monty was involved with the newspaper during the time of the Groundwork collective formation and was reminiscent of the folks involved in the two rad bookshops:

Do you remember Rick Nadeau? I know he was in the original collective and was on the Groundwork side of the split. The original collective was named the Changing Times. The group that moved downtown kept that name after the split. One of my housemates, Raul Contreras, was part of the group that moved downtown.

It would be good if somebody searched out founding members and pulled together a history. Nadeau is deceased already. I have no idea if other members are already gone. Clock is ticking.

The original collective was actually born out of a meeting called by the North Star newspaper collective (later New Indicator). The meeting was held at Lower Muir Commons, in the conference room next to the newspaper office of the time. I attended the first two meetings and then stopped, having decided my priority was the newspaper and that working on a bookstore would be too much added energy.

I remember there being an announcement in our newspaper about the first meeting to talk about forming a bookstore collective. Unfortunately, not all of our back issues are digitized by UCSD Special Collections, so it will require making a trip there to go through the microfiche collection to find it. I also remember that the first name given to the bookstore was North Star Bookstore. That didn't last more than a few weeks, however, before people decided on Changing Times. (The name North Star Bookstore did not last long enough to be what was the public name when the store did open. It did open as Changing Times. The North Star Bookstore name was only in the planning phase, and a result of the planning meetings having been called by the North Star newspaper collective.)

It indeed would be good for somebody to search out founding members. Maybe even members in those crazy decades of the 80's and 90's.

I guess when your strategy is social revolution, recording the personal efforts for future generations doesn't seem an important task, but running a bookshop and community center for 43 years through non-hierarchal, anticapitalist means, and an ever rotating student body is a helluva accomplishment that could use more documenting. If you have worked, volunteered, or fellow traveled at Groundwork Books since 1973 please write us and share some of your memories: groundworkbookscollective@yahoo.com

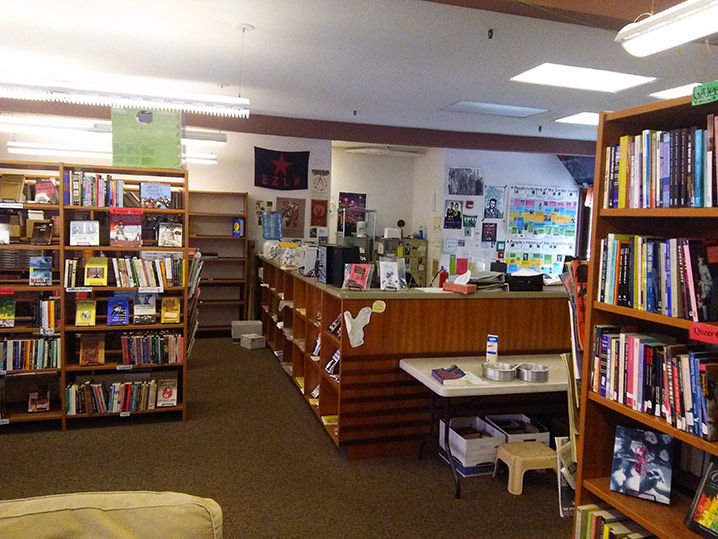

Photo: Groundwork Books in 2016, located in the UCSD Old Student Center

Comments